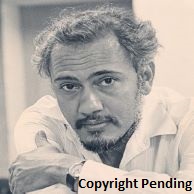

Distinguished scholar and champion of Jamaican art

Art historian David Boxer was just twenty-nine years old when, in 1975, having just completed his dissertation at Johns Hopkins, he returned to his native Jamaica to become director and curator of the newly established National Gallery of Jamaica. His doctoral studies at Homewood had concentrated on the modernist painter Francis Bacon, one of the most important British painters of the twentieth century, whom Boxer had spent two weeks interviewing the previous year. Bacon’s psychologically intense, semi-abstract figurative imagery later influenced Boxer’s artistic efforts, which included paintings, collages, and mixed-media installations—often depicting literary and history-related themes, including slavery.

Substantially broadening his fellow Jamaicans’ understanding of their own culture, Boxer’s first exhibition for the National Gallery portrayed Five Centuries of Art in Jamaica, where he argued that art on the island had a much longer history than had been recognized previously. By the time he stepped down as director in 2013, Boxer had mounted more than fifty major exhibitions of Jamaican art, including one for the Smithsonian in 1983 that later formed the basis for the National Gallery of Jamaica’s first permanent exhibition. Boxer also steered the expansion of the museum’s holdings from about 230 works in 1974 to more than two thousand.

As a private collector, David Boxer amassed one of the most comprehensive collections of Jamaican art, photography, and furniture, as well as an exceptional collection of rare art books. Boxer also encouraged the efforts of Jamaica’s untrained, self-taught artists who created their paintings, sculptures, and carvings in the rural towns and villages where they lived. He called them “Intuitives,” and believed they helped to shape Jamaica’s national cultural identity. “Theirs is not ‘art for art’s sake,” he maintained, “but rather, as someone once described African art, ‘art for life’s sake.’”

Regarded as a leading scholar of art in the Caribbean region and arguably the most eminent authority of Jamaican art, Boxer left a distinguished legacy. In August 2016, Jamaica’s prime minister bestowed the Order of Jamaica (considered the equivalent of British knighthood) on David Boxer, acknowledging that he was being recognized “not just his personal artistic genius but even more so for what you have done for countless others in your unyielding passion to foster the growth of Jamaican art.” Writing about his “colleague, mentor, and friend” not long before Boxer died, art historian Edward M. Gomez declared Boxer “a towering figure in the recent intellectual history of the Caribbean region, whose work as an educator and activist helped shape the modern cultural identity of his small nation in the post-colonial era.” In their final conversation Boxer told Gomez, “We make art because we have—or we think we have—something to say and because we hope that, somehow, it will endure.” The pioneering researcher, thinker, collector, teacher, and working artist was seventy-one years old when he died at the end of May 2017.