IRB Profiles

-

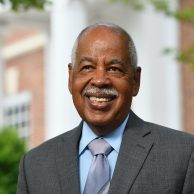

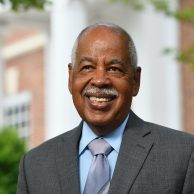

Davis, James

Healing with Dignity, Inspiring Others

Davis,

James

Davis, James

Healing with Dignity, Inspiring Others

Dr. James Davis entered the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine after spending time as an undergraduate at Wesleyan University and graduated from JHSM in 1974. Before his lifetime of work as a conscientious and caring physician, infectious disease specialist, and champion for the better treatment of Blacks in healthcare, Davis was born in Little Rock, Arkansas to parents who were both educators. Davis subsequently spent time moving place to place, from Washington D.C. to California; during these formative years, Davis gained a wealth of perspective on the difficulties African-Americans experienced across the country as the Civil Rights Movement happened around him throughout his formative years. This includes personally knowing members of the Little Rock Nine and being recruited to Wesleyan, and then attending Johns Hopkins as one of the few Black students on campus through the 2-5 program, a program that allowed exceptionally performing students to begin medical school after a transitional first year.

Davis commented on how moving from the intense segregation of Arkansas to the less overt discrimination of D.C. gave him hope, such as seeing “African Americans working in department stores… working for the US government; that sort of inspires you, because you can see that they could do it, and then you feel, “Well, I can do that too.”” However, after gaining early admittance to the Johns Hopkins Medical School at age 20, Davis noticed a lot of Black students struggling and being treated unfairly and he quickly stepped into the role of mentor and advocate; this was during a time where there were only 13 Black medical students and no Black faculty members.

Davis says the faculty members were determined to prove that he and his Black peers did not belong, and Davis saw that the discrimination had also infected the nurses and doctors in the community as well, as he worked in the Baltimore community as a medical student. These experiences helped him realize his life’s ambition, notably wearing a suit to graduation instead of a cap and gown as an individual protest to the prevalent racism he experienced at Hopkins. After graduating, time and again, Davis confronted racism within the medical community and the struggles of working in an extremely difficult and limited healthcare system; he says he was, “exposed to a tremendous amount of racism, not only me but to a lot of patients – I saw a lot of disrespect.” Davis then went on to work at the Harlem Hospital in New York, Howard University Hospital in D.C., multiple private practices, supported the Trans-Africa and anti-apartheid movement with Randall Robinson, served on multiple medical boards, and worked across the country for over 45 years before retiring, as a trailblazing physician serving Blacks every step of the way. He now serves as the Medical Director of his wife’s Home Care Agency, supporting elder care in D.C.

-

DeCosta-Willis, Miriam

Invincible scholar

DeCosta-Willis,

Miriam

DeCosta-Willis, Miriam

Invincible scholar

While Miriam DeCosta–Willis experienced the challenges of “being a black woman in a white man‘s world,” her life story demonstrates her ability to transcend those challenges. The child of two college professors, she grew up in the South but moved north in 1950 to help integrate Westover School in Connecticut. She describes her two years there as painful, yet she left the school with high honors.

After earning a bachelor‘s degree from Wellesley College she earned both her master‘s degree and in 1966, she earned a doctoral degree at Johns Hopkins. After obtaining her degree, DeCosta–Willis was appointed the first black faculty member at Memphis State University.

Throughout her 40-year career in education, DeCosta-Willis, a Spanish language and African-American studies scholar, held administrative and faculty posts at Howard University, George Mason University and University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

Now retired, she remains a lifelong civil rights activist and writer. In addition to serving as co-founder of the Memphis Black Writers’ Workshop, she has published several books.

Dr. Miriam DeCosta-Willis died January 7, 2021

Read University of Memphis Press Release

-

Dilsworth, Shirley

Legal go-getter

Dilsworth,

Shirley

Dilsworth, Shirley

Legal go-getter

Raised by a widowed mother facing health issues, Shirley Dilsworth moved from New Jersey to Baltimore as a young girl. As she was about to graduate from Western High School, she was invited to apply to Johns Hopkins and was admitted. It was the fall of 1970, the first year that Johns Hopkins began accepting female undergraduates, and among the 90 admitted were five black women: Dilsworth, two fellow freshmen, Karen Freeman Burdnell and Gail Williams, and two transfer students, Lynn Parker and Barbara Wyche.

A focused student, Dilsworth lived at home and worked part time at the Enoch Pratt Free Library throughout her college years. She remembered a sixth-grade teacher telling her that she could not achieve her dream of becoming a lawyer. Instead of discouraging her, such comments fueled her determination to succeed.

Following her graduation from Johns Hopkins, Dilsworth earned two law degrees and worked for many prestigious companies. She is currently the divisional vice president of human resources for Nordstrom’s Credit Division and Corporate Center and an active community leader.

-

Edgerton, Martha

Conservator of books and the black community

Edgerton,

Martha

Edgerton, Martha

Conservator of books and the black community

When author Alex Haley came to Maryland to unveil a memorial to his legendary ancestor Kunta Kinte, many fans sought his autograph. Martha Edgerton was probably the only one who had him sign a copy of his masterwork, “Roots,” that she had personally rebound.

The theme of conserving treasures permeates Edgerton’s life and professional career. After completing a five-year apprenticeship at the John Hopkins Milton S. Eisenhower Library, she became the program’s first graduate in 1980. That same year, Edgerton represented the American Research Libraries Group in England at the first international conference on preservation/ conservation. She continued her professional growth as a member of local and national preservation organizations and through an internship in the rare books section of the Library of Congress.

For more than 30 years, Edgerton worked as an integral member of the Eisenhower Library staff, as a book and paper conservator and as a teacher and organizer in several consultancy, internship and workshop programs supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities. While working at the library, she conserved many materials of great value including a very rare four-volume set of Audubon’s “Birds of America” and a 16th century “Luther Bible” and she took a leadership role in developing and participating in the library’ exhibits program.

Edgerton’s interests extended beyond the library to a different type of conservation, that of uniting and addressing the needs of the black community at Johns Hopkins. “As an attendee of the very first public meeting for the formation of the Black Faculty and Staff Association, I was in full agreement with its mission and became actively involved,” said Edgerton. She became an executive board member and was elected the organization’s president in 2005. During her presidency, she helped strengthen the organization’s funding from Johns Hopkins, enhanced its programming by bringing in notable presenters such as civil rights activist Myrlie Evers-Williams, continued efforts to persuade the university to add an African studies curriculum and encouraged other Johns Hopkins campuses to participate in the BFSA.

Edgerton left Johns Hopkins in 2008 to manage the Preservation Unit of the Enoch Pratt Free Library. She volunteers at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Benjamin Banneker Museum. She teaches workshops related to book and paper preservation/ conservation, bookbinding, and BookArt-this last her personal passion.

-

Etienne-Cummings, Ralph

A Brilliant Mind

Etienne-Cummings,

Ralph

Etienne-Cummings, Ralph

A Brilliant Mind

Ralph Etienne-Cummings developed his passion for math and science as a young boy growing up in his native Seychelles, an archipelago of islands northeast of Africa, and in England where he lived for long periods of his youth with his grandmother. The product of teenage parents, including a mother who stressed education, Etienne-Cummings turned out to be a bright child with a knack for fixing things and figuring out problems. In the U.K., he attended a strict Benedictine school where he rose to be a top student in his class and excelled as an athlete.

The year before he graduated from high school, Etienne-Cummings moved with his family to New Orleans where he continued on a path that would eventually lead him to Johns Hopkins University. Here, he is a professor of electrical and computer engineering in the Whiting School of Engineering – one of only a few black faculty in the school. Etienne-Cummings landed at Hopkins by way of Lincoln University near Philadelphia where he majored in physics and took an interest in electronics. He went on to the University of Pennsylvania where he earned his master’s and doctoral degrees in electrical engineering.

While in undergraduate school, Etienne-Cummings started thinking about research as a career. His focus would be where biology and electronics meet. One area where Etienne-Cummings has made a name for himself at JHU and among engineers, and federal funding agencies, is with his years-long quest to develop a spinal implant that will help people paralyzed from the waist down regain movement and sensation. His research interests also include systems and algorithms for biologically inspired and low-power processing, biomorphic robots, applied neuroscience, neural prosthetics, and computer integrated surgical systems and technologies. He holds seven patents and has mentored over thirty-five students at the graduate level.

At Hopkins, Etienne-Cummings has sponsored a number of diversity and mentoring programs, including serving as co-chair of the Diversity Committee, and as a mentor of the Whiting School’s Robotics Club. Etienne-Cummings has also served as a consulting engineer for several technology firms, including Nova Sensors, Inc., and Panasonic N. American & Corporation.

Aside from his science, Etienne-Cummings feels strongly about bringing more people of color, particularly African Americans, into the engineering fold. He is also among those at Johns Hopkins who have been asked by university leadership to help recruit black faculty to JHU, and to the Whiting School. “It’s super important,” he said. “In engineering and the university in general we have to do better. Having a diverse faculty matters. You have to have role models. Otherwise, how do you convince yourself that you are good enough to be in places like a Hopkins or a Stanford?”

-

Freeman, Michael

Champion of Change—Black Faculty and Staff Association Founder

Freeman,

Michael

Freeman, Michael

Champion of Change—Black Faculty and Staff Association Founder

The Black Faculty and Staff Association (BFSA) came together, as so many advocacy groups do, over lunch and a conversation. Lunch was at the Polo Grill, then a restaurant across from Homewood Field, and the people who had gathered to talk were black senior staff members concerned about the lack of support for people of color at Johns Hopkins.

Toni Moore-Duggan, one of the participants, recalled how that lunch and subsequent discussions among the staff members led to their decision in 1995 to establish the BFSA.

“After graduating from Johns Hopkins and while working there, it became evident that there was no voice or forum for black people having difficulties here,” said Moore-Duggan, a certified nurse practitioner who worked at the institution for

years.

At first, Moore-Duggan said, she and the other staff members were not sure if anyone would buy into efforts to create a forum for people of color, but they did. Seventeen years later, the group is not only going strong but has expanded its mission: to help foster a culture of collaboration by promoting and enhancing the identity and professional welfare and growth of faculty, staff and students through collaborations, community service, education, research and cultural activities. The BFSA has also charged itself with being a crucial resource for the continued success of Johns Hopkins through the development and cultivation of relationships with key leaders of the institution.

Michael Freeman, a former senior academic adviser at Johns Hopkins University, now serves as vice president for student affairs at Tennessee State University. In 2010, he participated in the Harvard University Graduate School of Education’s Institutional Educational Management Program. He earned a doctorate from the University of Maryland, College Park.

-

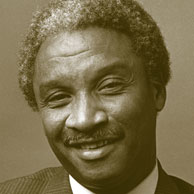

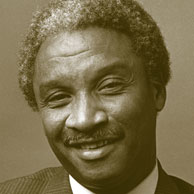

Gamble, Robert L.

Legacy-building neurosurgeon

Gamble,

Robert L.

Gamble, Robert L.

Legacy-building neurosurgeon

In becoming one of the first two black people to earn a medical degree from Johns Hopkins, in 1967, Robert Gamble was fulfilling what he saw as a family legacy. He grew up hearing the story of how his grandfather, Henry Floyd Gamble, graduated with a medical degree from Yale University in 1891, paying his way through school by working as a waiter and janitor.

Before entering Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Gamble had earned a bachelor’s degree, magna cum laude, from Howard University in 1963 and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa.

Gamble, whose only brother also became a physician, worked in New York as a neurosurgeon.

-

Gaston-Johansson, Fannie

Globe-trotting nursing innovator, researcher and educator

Gaston-Johansson,

Fannie

Gaston-Johansson, Fannie

Globe-trotting nursing innovator, researcher and educator

Medical professionals ask patients how they feel, where it hurts and how much, and patients struggle to answer the questions. But the Painometer, a pain assessment tool developed by Fannie Gaston-Johansson, helps patients better describe their pain to medical professionals and therefore receive better care.

A commitment to improving pain and symptom management and eliminating health disparities forms the foundation for Gaston-Johansson’s career at Johns Hopkins University. Named the Elsie M. Lawler Professor in 1993, she was the first black woman to become a full professor at Johns Hopkins. In 2007, she was appointed the first chair of the School of Nursing’s Acute and Chronic Care Department. Gaston-Johansson directs the Center on Health Disparities Research, leads the international and interdisciplinary Minority Global Health Disparities Research Training Program and is co-director of a postdoctoral training program in breast cancer research for underserved and minority women.

An opportunity to study in Sweden in the late 1960s served as the catalyst for a parallel career in that country. After a variety of nursing and faculty positions there, Gaston-Johansson served from 2001 to 2005 as the first female dean of Gothenburg University, the largest university in Scandinavia. A year before she became dean, she had inaugurated the university’s doctoral program in nursing. In recognition of her achievements, in 2005 she became the first nurse elected to the Royal Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities, a Swedish organization established in 1753. Gothenburg University held a two-day tribute honoring Gaston-Johansson in 2006, which included a symposium and the presentation to her of “The Apple of Knowledge.”

-

Glenn Sr., Chance M.

Visionary Engineer and Creative Futurist

Glenn Sr.,

Chance M.

Glenn Sr., Chance M.

Visionary Engineer and Creative Futurist

He has been described as a jack of all trades and a master of some. Glenn characterizes himself as a creator, a technologist, a futurist and a visionary. In fact, he is all of this thanks in no small part to his accomplished career – a career guided by his education at the Johns Hopkins University. Glenn, now a tenured professor and dean of the College of Engineering at Alabama A&M, received his master’s and Ph.D. degrees in electrical engineering from Johns Hopkins. He earned his undergraduate degree in electrical engineering from the University of Maryland College Park. He also studied management development, earning a certificate, at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

With his paper in hand, Glenn began his career at the Army Research Laboratory in Maryland where he designed microwave and radio frequency devices for a range of defense-related applications. At the lab, he also became involved in signal processing and the study of non-linear dynamical systems. He left the lab to co-start an engineering company. In 2003, Glenn joined the faculty at the Rochester Institute of Technology, where he was a tenured professor. Five years later, he was named associate dean of graduate studies at RIT. Throughout his academic and professional career, Glenn, who is well-published and has given talks nationally and internationally, has several patents to his name.

In 2012, Glenn was named dean of Alabama A&M’s College of Engineering, Technology and Physical Sciences, where he continues to position the university through its plan to prepare students and researchers to meet the global needs of the 21st century. In his role as dean, Glenn works with faculty to develop new programs in engineering and applied science and he leads the university’s efforts to collaborate with industry and other institutions of higher learning around the world to grow research in materials science, image and signal processing, alternative energy and other areas of global significance. But Glenn isn’t all work and no play. In addition to his academic and professional accomplishments, Glenn is a singer and songwriter who has both written and recorded songs. One of his songs was nominated for a Grammy award.

-

Golden, Sherita Hill

Physician-Scientist Confronting Social Inequities

Golden,

Sherita Hill

Golden, Sherita Hill

Physician-Scientist Confronting Social Inequities

During medical school, Sherita Hill Golden “developed a passion for inner city medicine,” particularly relating to diabetes among people of color. When she arrived in East Baltimore for her residency in July 1994, the young doctor appreciated the presence of so many Black support staff. “They were very proud when they saw a Black doctor, even if you were an intern,” she recalled. “If you stepped on the elevator and they saw the M.D., they were like, ‘Oh, Dr. Hill, I hope you’re having a good day.’ They would walk you to your car at night to be sure you were safe. They would make sure at holidays that you had food.” In fact, it was a unit clerk who introduced her to her future husband, pediatrician and neonatologist Dr. Christopher Golden. “One of the things that makes Hopkins such a special place is not just the intellectual capital of the faculty but the dedication of the staff, it’s those human relationships that people don’t always see that make a difference for many of us here.”

Golden’s principal clinical and research interest is understanding the effects of chronic psychological stress “whether it’s from racism, depression, or environmental influences, and how that increases a person’s risk for diabetes and heart disease.” Recognizing a correlation between chronic stress and depression and the risk of developing diabetes, she employed the tools of population science to identify novel hormone risk factors as contributors to diabetes. “As a teacher, I wanted to train other physician-scientists how to study the hormonal risk factors in large populations because once you’ve figured out the risk factors, the next question is, how do you develop interventions to change hormonal responses to prevent or treat diabetes?” The system of checks and balances now in place for patients with diabetes throughout the Johns Hopkins Health System resulted directly from Golden’s clinical, research, and educational efforts.

When Freddie Gray was arrested in April 2015, Dr. Golden had been on the faculty for twenty years and executive vice chair of the Department of Medicine for two months. With her department chair’s support, she initiated a Journeys in Medicine discussion series to promote honest dialogue about everyday lived experiences of racial injustices faced by doctors, nurses, administrators, and support staff from minoritized communities. The department also welcomed East Baltimore civic leaders who directed conversations with medical faculty and staff and explained that members of the community sometimes felt they were treated with disrespect when they came into the hospital. They conveyed the community’s willingness to participate in research projects, but admonished, “don’t disappear when it’s over, take the resources, and never tell us what happened.” The series inspired major changes in the Department of Medicine.

In her current role as vice president and chief diversity officer for all of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Golden partners with administrative peers on other Hopkins campuses to align their approach to diversity awareness training for all staff and students. “After the murder of George Floyd, we worked together across the university and Johns Hopkins Medicine to understand the contribution of structural racism on society,” she recalls. “Just the concepts: What does structural racism look like in health care, in housing, in education?” Similarly, she and her team collaborate with the Office of Government and Community Affairs to support workforce diversity and health equity initiatives, and frequently testify before legislative committees as content experts on various related subjects. “We need more race and ethnic diversity, but we are making progress,” Golden recognizes. “If you treat everybody the same, inequity will persist because everybody needs something different. We aren’t all starting at the same place.”

-

Grovogui, Siba N.

Justice seeker

Grovogui,

Siba N.

Grovogui, Siba N.

Justice seeker

In Guinea, the country of his birth, Siba Grovogui excelled academically and became a judge while still in his 20s. But he soon discovered that the political structure in Guinea placed great constraints on judges and hindered justice. In moving to America and becoming an international relations and political theory professor, Grovogui found a more effective way to write and talk about justice. “I want to change how we think of ourselves as humans,” he has said. “We have to know our world. Social sciences really have to be about us in the world. Not what we in America can get from the world.”

In the process, Grovogui is helping to change the way Johns Hopkins teaches international relations. Through his commitment to the Institute for Global Studies, doctoral students have greater opportunities to do field work and to learn from diverse experts in various fields.

-

Guess, John F.

Catalyst for campus change—Black Student Union Pioneer

Guess,

John F.

Guess, John F.

Catalyst for campus change—Black Student Union Pioneer

Empowered and inspired by the civil rights movement, students John F. Guess and Bruce Baker presented 12 demands to Johns Hopkins University administration in 1967. They sought such changes as increased black student enrollment and black faculty recruitment, a library section for black authors, and Johns Hopkins-Morgan State mixers.

A year later, Guess, Baker and others established a Black Student Union at Johns Hopkins. Although similar groups had already formed at other university campuses, students at Johns Hopkins found their initial requests for official recognition rebuffed. The student council expressed concern that this student union would be seen as hostile and divisive. Continued and mounting pressure from Guess and Baker caused the student council to reconsider its decision and grant official status in 1969.

The Black Student Union remains an influential group at Johns Hopkins, promoting diversity, respect, and understanding. The group also hosts events and lectures, organizes community service projects and works to improve the climate for black students at Johns Hopkins.

Its founders continue to serve as prominent community leaders.

Guess, a native of Houston, became the first BSU chairman and the first black president of the university’s student council. He is chief executive officer of the Houston Museum of African American Culture, managing consultant at The Guess Group Inc., a real estate services company and a Partner in the Dallas-based Access Seminars and Consulting Services. He is an active art collector whose works have been shown in museums across the country and in Europe.

-

Hall, Joseph S.

University-community convener

Hall,

Joseph S.

Hall, Joseph S.

University-community convener

For most of his career with Johns Hopkins, Joseph S. “Jakie” Hall was a convener, building and maintaining bridges between university leaders, students, the community and faculty, as well as people in the U.S. government and in other nations.

Hall came to Johns Hopkins in 1973 as dean of students, and, with the simple act of accepting this appointment, he became the first black dean on the Homewood campus. Five years later, Hall was appointed dean of academic services and in 1982 became senior assistant to the president.

In 1986, Hall took on his last position with Johns Hopkins as its vice president for institutional relations. One of his first major projects was to lead a Human Climate Task Force, charged with addressing such issues such as the status of women, academic dishonesty and faculty-student relations. Dr. Steven Muller, then university president, charged the task force with finding a way to deal with these sensitive issues in a spirit of respect, civility and cooperation. The task force presented its findings to Muller in 1987.

In his five years as vice president, Hall continued to address the issues explored by the task force and to promote minority faculty and student recruitment; coordinate the university’s response to student protests over its investments in companies doing business in South Africa; serve as liaison to the International Fellows Program of the Institute for Policy Studies; and manage university projects with the Baltimore City Public School System, such as the Johns Hopkins-Dunbar High School project.

-

Hargrow, Minnie

Ambassador in the President’s Office

Hargrow,

Minnie

Hargrow, Minnie

Ambassador in the President’s Office

On her first day at work in the cafeteria at Johns Hopkins University’s Homewood campus, Minnie Hargrow looked around to see three buildings, male students wearing suits, and a student body and faculty that were all white. The year was 1946, and Hargrow and her husband had just moved to Baltimore following his return from service in World War II.

For 34 years, Hargrow-who quickly became known to all as “Miss Minnie” continued to work in the cafeteria providing physical and emotional nourishment to the university community, as she witnessed that community becoming larger and more diverse. At the same time, her desire to work in the President’s Office grew stronger.

In 1981, Hargrow was offered and accepted the position of assistant to the president, a position she kept until her retirement in 2007. Her constant smile and warmth permeated the office, yielding strong positive first impressions for countless visitors.

-

Haynes, M. Alfred

Architect of social justice in medicine

Haynes,

M. Alfred

Haynes, M. Alfred

Architect of social justice in medicine

As a physician, mentor, professor and dean, M. Alfred Haynes, now retired, dedicated his career to reducing health disparities and improving health care systems in the U.S. and around the world. After joining the International Health Department at Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health in 1964, he went to India on an assignment in collaboration with the United States Agency for International Development. Tasked with improving the Department of Social and Preventive Medicine at the Medical College in Trivandrum, Kerala, Haynes created a system to place medical interns in rural primary health units for more meaningful field experiences. He also conducted research on background radiation and family planning services. Returning to Johns Hopkins in 1966, Haynes applied his lessons learned to create a program for teachers of community medicine and to develop a comprehensive health planning program. International students used principles learned in these programs to enhance health care around the world. In addition, Haynes published studies regarding opportunities for black health care professionals and contributed to the “Hunger USA” study. His research into racial health disparities led to the creation of the National Medical Association Foundation whose mission is to address the health needs of inner city residents. Haynes was the foundation’s first director. Haynes declined to become a full professor at Johns Hopkins so that he could accept the challenge of helping to establish the Charles Drew Postgraduate Medical School in the Watts area of Los Angeles in 1969. He ultimately became the dean and president of that school.

-

Hildreth, James

Advocate for Diversity in the Laboratory

Hildreth,

James

Hildreth, James

Advocate for Diversity in the Laboratory

A personal letter from pioneering cardiac surgeon Levi Watkins encouraged Harvard senior James Hildreth to apply to Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. After deferring his acceptance to pursue a PhD in immunology at Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship, Hildreth came to Baltimore in 1982—joining a cohort of fourteen African-American medical students recruited by Watkins. “We all understood the significance of being at Johns Hopkins in unprecedented numbers. When we got onto the wards, we loved that the staff and housekeeping were all people of color and you could see the sense of pride they had in seeing us in our white coats,” Hildreth recalled.

Hildreth was invited to join the pharmacology and molecular sciences faculty in 1987, the same year he graduated from medical school. “It was stressful. You have to recover your salary from grants in the Basic Sciences at Hopkins. I think the pressure cooker helped me because now it’s easy, having been in that environment.”

The start of Hildreth’s professional career coincided with the HIV/AIDS crisis. “It became clear that this was going to be the challenge of our time as immunologists,” he explained. “As my project moved forward, I had to retool and relearn some things. At Hopkins, you could walk down the hall and find an expert and they were always willing to sit down and talk with me about their science.” He was a singular presence in his discipline. “I was the only Black faculty member out of over two hundred in the Basic Sciences at the time,” Hildreth remembered. He remained so when he became a full professor with tenure in 2002, and even when he left Hopkins in 2005 to lead research on HIV/AIDs at Meharry Medical College School of Medicine in Nashville.

Still, Hildreth’s influence remains at Johns Hopkins. In 2009, the Biomedical Scholars Association inaugurated the annual Dr. James E.K. Hildreth Lecture in order to showcase a scientist “who reflects, supports and/or promotes diversity in the fields of biomedical research, public health, or nursing in an effort to educate the Hopkins community.” The event is a fitting tribute for Hildreth, who gratefully recalls “the quality of students that Hopkins attracts. It helped me to be surrounded by brilliant young people.” He was pleased on a recent visit to see increased diversity on the East Baltimore campus.

Today, Dr. Hildreth is president and CEO of Meharry Medical College School, one of the oldest and largest historically Black academic health science centers in the United States. He is proud that Meharry graduates frequently perform their residencies at Johns Hopkins and other top-ranked medical institutions.

After more than thirty years of HIV/AIDS research, Hildreth pivoted in 2020 and joined Operation Warp Speed during the Covid-19 pandemic to oversee vaccine trials at Meharry. He also served on FDA committees that approved vaccines and drugs for treatment of the virus. “I was called upon by lots of organizations to explain the science. I did 109 press conferences. I was particularly interested in making sure that minorities understood because they were most at risk. If you are Black in the United States, you have every reason to be suspicious, based on Tuskegee and eugenics. People have thanked me, saying their loved ones would not have taken the vaccine were it not for me explaining the science.”

“I am committed to making sure there is diversity both in access to health care and in those who provide it,” Hildreth stressed. “I’m especially passionate about making sure we capture all the genius we have in this country. I think about all the brown and black kids out there who might be the ones to solve problems for us but they’ll never get a chance,” he explained. “I’ve ended up training about twenty PhD students and all of them are super bright and super motivated. The truth is, even today with some of the students I’m mentoring or co-mentoring around the country, I learn more from them than they learn from me.”